Using Fire to Manage Natural Landscapes

Measuring success in prescribed fire programs can be tricky. The obvious way is to count acres, which is very effective in measuring the work completed. Measuring the quality of burns is a little more challenging, but equally valuable. This is where I can contribute, as a biologist, toward District 4’s prescribed fire program.

The Need for Fire

The need for fire in natural pyric ecosystems is not a complicated subject, but can be complicated by over-thinking the matter, as well as the restrictions placed upon fire practitioners. Many natural communities (or group of plants and animals in their physical environmental) in Florida and elsewhere require frequent fire to thrive. Some grass and herb species require fire to flower.

Fire comes naturally in the form of lightning during the spring, when most vegetation is at its driest. These evolutionary forces have led the vegetation to become adapted to fire. The Southern slash pine and longleaf pine are extremely fire-tolerant (meaning they do not readily ignite and they are well-adapted to survive fires) and their seeds need contact with the mineral soil and open sunlight that fire provides in order to germinate.

Animal species also are dependent on fire to maintain their habitats. With the exclusion of fire, or fire being applied consistently in the wrong season, ground cover diversity and abundance are negatively impacted, natural communities degrade, their biodiversity plummets and their value as a natural area diminishes.

Simple Philosophy

I try to incorporate a simple philosophy of improving the natural landscape when embarking on the annual planning process. By looking at the historical burn data, we can see the season of the last fire; its intensity (good and bad); weather conditions like relative humidity, days since rain, wind speed and direction; and if indeed the resource management objectives were met and, if not, the reasons why.

With this information we can write broad objectives to improve on the last prescribed fire, which hopefully will set in place a trend that should result in well-maintained and biodiverse pyric landscapes.

Planning for Success

In any successful prescribed fire plan, one must start with accurate data. That comes in the form of updated natural community maps in the park’s unit management plan (UMP), natural community information found in the Florida Natural Areas Inventory (FNAI) and historical burn data (day of burn reports) in the Natural Resource Tracking System (NRTS).

In District 4, we have 75,552 fire-type acres with 53,295 in rotation. Our target acres range from roughly 20,000 acres to 48,000 acres to be burned annually, and this is spread over 26 state parks. Developing the annual plan for the district can be a daunting task but always an enjoyable one.

The dedicated burn staff I work with vary in experience, from first-time burn bosses to the most experienced burn bosses in the Florida Park Service. Knowing that, I apply myself to parks where my help is needed the most.

Site Visits are Vital to Success

After the annual plans are entered into NRTS by the respective managers, I check the information for accuracy and see if any obvious oversights have been made. I then make arrangements to meet the burn bosses at their parks to go over their plan, prescription and burn preparation needs they may have. The prescription addresses the goal of the burn and incorporates all the operational activities to ensure success. I take the opportunity to walk the individual management zones with the prescribed burner and discuss the natural communities, burn history and, most importantly, the resource management objectives outlined in the prescription.

We discuss how our resource management objectives can be met by understanding how the prescribed fire is going to move through the landscape, which is relatively predictable, with specific weather conditions, time of year, live fuel moisture and possible drought conditions on the day of burn. Once we understand the objectives and how we can or cannot meet them, we can adjust our planning, either the objectives or the burn window, to have the best possible outcome.

Conducting the Prescribed Fire

Once that’s done, we conduct normal (if that’s a thing) prescribed fire activities and treat as many acres as we can in the framework we have laid out. I help as much as I can during the day of burn and try to conduct my own burns whenever I have the opportunity. There is always value in getting boots on the ground and participating in the burns and not relying on the day of burn reports to accurately gauge success.

Rewards — One Year Later

One the most rewarding aspects of the entire process is participating in the one-year post-growing season evaluation and witnessing first-hand the successful prescribed fire’s impact on the landscape. This includes monitoring listed species such as the Florida scrub-jay that make their way back into zones where they have not been seen before and recognizing the diverse ground cover that returns after years of fire exclusion.

About the Author

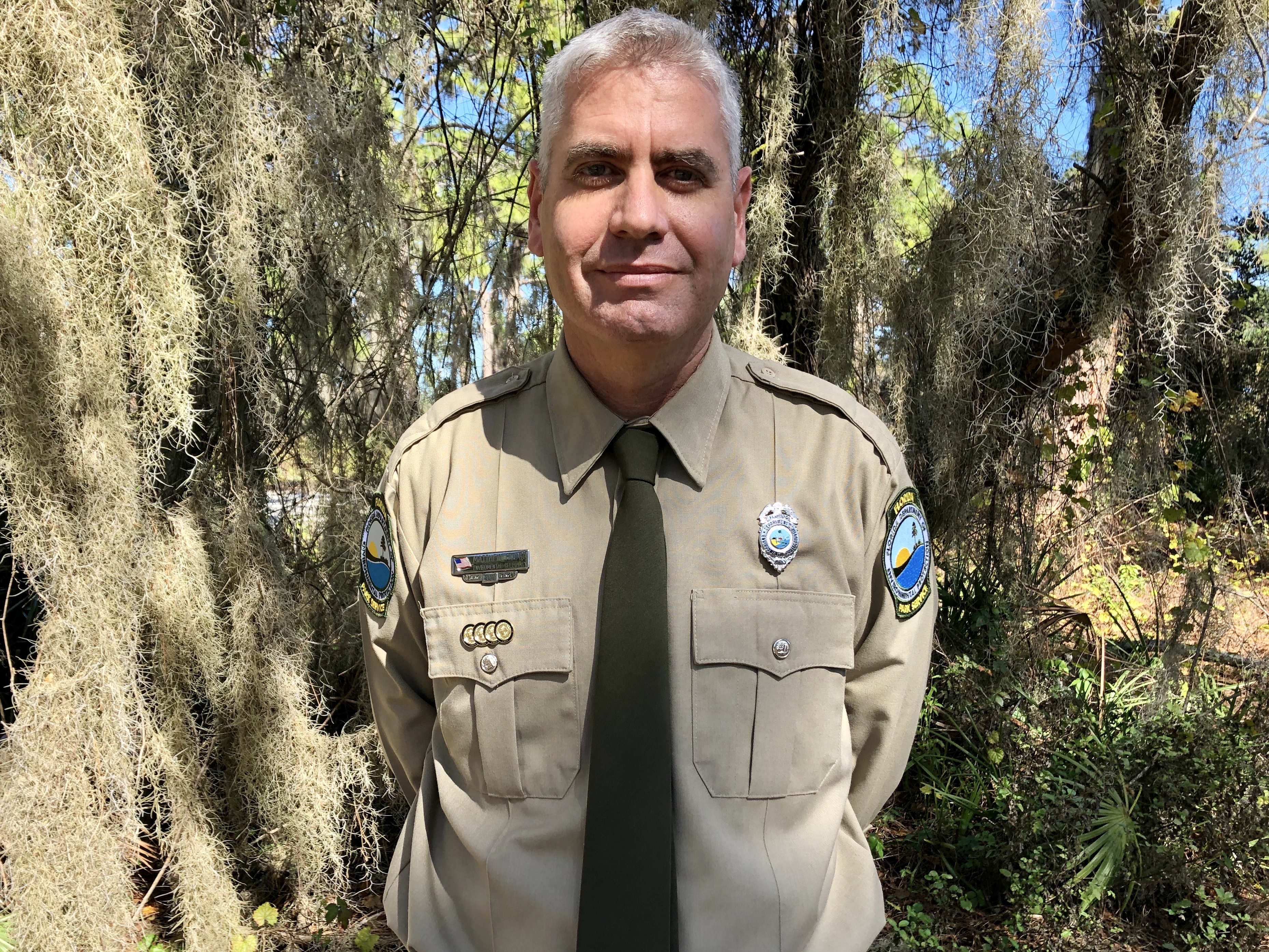

Matthew Hodge earned a Bachelor of Science Honors degree in Zoology, Limnology and Botany from the University of Johannesburg (previously known as RAU). He started working with the Florida Park Service in 2007 as a seasonal employee at Oscar Scherer State Park. He worked primarily as a toll collector and completed park maintenance duties on the weekend. He started working as a park ranger in 2009.

With previous prescribed fire experience, he did well in the park’s burn program. In 2014, he started as an environmental specialist, and took on the duties of assisting park managers with meeting their ecological goals as it pertains to prescribed fire management, coordinating mosquito control for the district, writing resource management components for unit management plans and assisting park staff with mapping. He also assists with wildlife issues, including maintaining the vertebrate database, conducting wildlife monitoring and research, and providing guidance on listed species habitat management. Matthew serves as a representative on relevant committees, stakeholder groups, advisory groups, land management reviews and management councils.

Matthew is married to Cherie Hodge. They live in Sarasota with their old dog, Buddy. His hobbies include photography, triathlons and travelling.

About The Biologists Tell the Story Series

In this series, we will learn a little more about our biologists as they share stories of their work in Florida’s state parks. The leadership and scientific research our biologists provide is essential for our legacy of conservation and land management. This series is an opportunity to connect these projects to the places where we ensure the health and sustainability of Florida State Parks.

Previous articles in the series can be found here.