Legacy of the CCC at Myakka

The Civilian Conservation Corps, or "CCC boys" as its members were nicknamed, had an integral role in creating many of Florida's state parks.

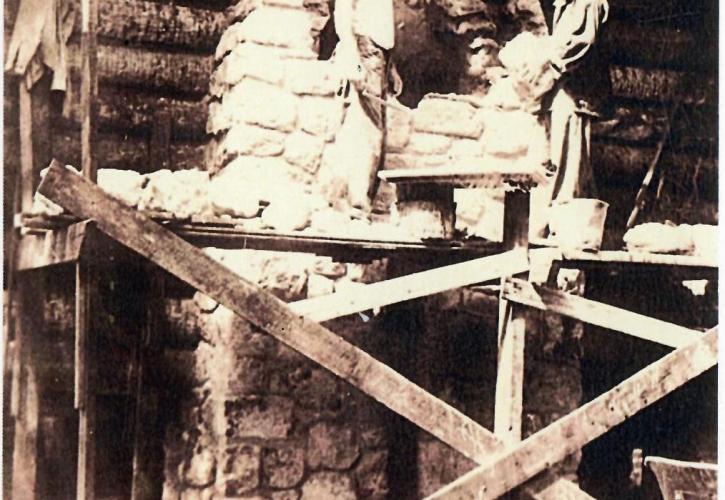

At Myakka, these hardworking men blazed trails, built bridges, dug the boat basin, erected a weir and constructed many buildings still in use today.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt established the Civilian Conservation Corps as part of his New Deal, economic-oriented legislation enacted in the height of the Great Depression. Roosevelt used the Army’s organization and materials to provide camps for CCC enrollees, earning them the nickname of "Roosevelt's Tree Army."

Desperate for economic relief, communities all across the nation petitioned to have land made into national and state parks by the CCC. Sarasota and the Myakka River Valley were approved for a CCC camp thanks to the work of Arthur Britton Edwards.

Edwards, an orphan who raised his six siblings, was a brilliant real estate marketer and the first mayor of Sarasota. He persuaded developers and urban socialites seeking pastoral beauty to move to a small town of fewer than 300 people. He worked with developer Bertha Palmer to build a railroad and irrigation systems.

As a result, Sarasota flourished.

Edwards also appreciated the innate natural value of the Myakka River valley. He described the land as “priceless heritage” and sought to preserve it. It had been Palmer’s cattle and swine ranch, but it fell into near abandonment after her passing. The inception of the CCC provided the perfect opportunity to protect this land.

First, Edwards petitioned the National Park Service to create a national park. However, federal officials were so inundated with requests that this one fell aside. Unwilling to give up, Edwards petitioned Florida State Forester Henry Lee Baker to make the land a state park. Baker obliged under one condition: Edwards needed to guarantee enough land in just two weeks.

Edwards’ first land acquisition was remnants of Bertha Palmer’s ranch. He struck a tax deal and acquired 17,000 acres for just 37.5 cents per acre from Palmer's heiress. Then he promised the Curry lands, which was farmland under foreclosure and was the most controversial undertaking. Governments were very hesitant to seize foreclosed farmlands in the Great Depression. However, because of the foreclosed status, Edwards was able to secure 6,000 acres for what became Myakka River State Park.

Finally, just at the deadline, Edwards sought one more area of land. Pursuing a hushed rumor, he approached two of Bertha Palmer’s sons, Potter Palmer and Honoré Palmer. They were considering a land donation in honor of their mother.

The discussed acreage was exceptional — it had higher elevation ideal for an ecosystem that is under water during the summer. Finally, after multiple meetings and much pressure from Edwards, the sons agreed to a 960-acre donation just two days before the deadline. In only two weeks, Edwards accumulated 25,000 acres (39 square miles), which was enough to establish Myakka River State Park.

In October 1934, the first CCC enrollees from South Carolina arrived in the wild Myakka River valley to begin work.

CCC enrollees were typically impoverished, unmarried men of about 18 to 25 years old.

Once recruited, they had their Army-run physical examination and signed up for a six-month term. If no alternate employment was available, an enrollee could renew three more times (for a total of two years). The Army provided housing, clothing, food and organization, while the Department of the Interior (and related interested parties) created the projects.

The first CCC enrollees at Myakka River State Park faced extremely tough conditions. There were no barracks, so they slept in tents. Sometimes, they would find rattlesnakes slithering through. Additionally, mosquitoes infested Myakka's swamplands, and some of the men fell ill to malaria. Sanitation and food also posed problems.

There were no plumbing facilities in the Myakka valley. In the first few months, about 50 men were labeled “ineffective,” mostly due to malaria and abandonment.

While these conditions might deter those of us accustomed to beds, air conditioning and bug spray, there was also plenty of appeal to joining the CCC.

At home, young men couldn’t find work, were forced to share food and cramped living conditions with parents and siblings, and were unable to access resources necessary for education and jobs. Although it took a few weeks, basic needs like housing and food were met at Myakka.

Joining the CCC meant provision of basic needs such as food and housing, and enrollees also had an abundance of opportunities for recreation and education.

Best of all, the "CCC boys" earned a salary. They worked for $30 per month, often sending $25 back home to their families and keeping $5 for themselves.

The army determined the schedule for enrollees. A typical day would go as follows:

- 6 a.m. - Wake up.

- 6:30 a.m. - Roll call and raising of American flag.

- 7 a.m. - Breakfast.

- 7:45 a.m. - Barracks inspection.

- 8 a.m. - Report to work assignment.

- Noon - Lunch.

- 4 p.m. - End of work, return to camp.

- 6 p.m. - Lowering of American flag, dinner.

- Afterward, job training, recreation time (sports, hikes, hunting, dances, etc.) and bedtime.

In their free time, many enrollees enjoyed the park through hiking, fishing and playing team sports. The enrollees could attend free, optional job training classes where they could learn skills such as welding and carpentry. Literacy and arithmetic were a main concern of CCC administrators, and literacy levels for enrollees soared thanks to the program.

The men had access to books, and many at Myakka participated in writing a newsletter. On most Saturday nights, they would have a dance, which young women from Sarasota were invited to join.

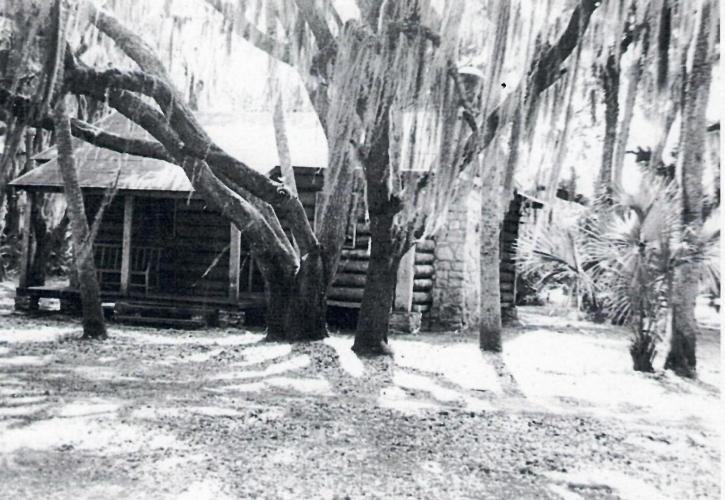

Still, the work remained arduous at Myakka River State Park, even after basic needs were met. The men paved the road, built bridges, strung telephone lines and blazed trails - all by hand. Myakka's CCC also constructed the South Pavilion and the Log Pavilion.

The current visitor center is a refurbished CCC-built horse barn. The CCC also built a park manager’s residence (which is still occupied by a staff member) and five rental cabins.

The boat basin was hand dug with iron shovels, and a weir on the Upper Myakka Lake was made by the CCC, though it has since been removed (read about it here). About a mile down the main road (originally paved by the CCC), visitors will come to a bridge. The original bridge here was hand-built by the CCC out of wood they had chopped down.

After working for the CCC, men could be hired in skilled trades. Many of them found a long-term career in the armed forces. Already adapted to a military-style schedule and fitness level, enrollees were quick to enlist after the attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941. The CCC was part of the reason that the U.S. was so able to quickly and successfully mobilize into WWII.

The CCC's story is inspirational. Young men worked hard, fed their families, became educated, learned skilled trades and made a nationwide impact protecting the environment. There is much to celebrate. It is important, however, to not remember just the positive impacts.

A comprehensive understanding of the CCC at Myakka River State Park is barren without a discussion of some of the negative repercussions of their work. While their efforts in making this area accessible to humans is laudable, they also caused damage to the environment - sometimes knowingly and sometimes not.

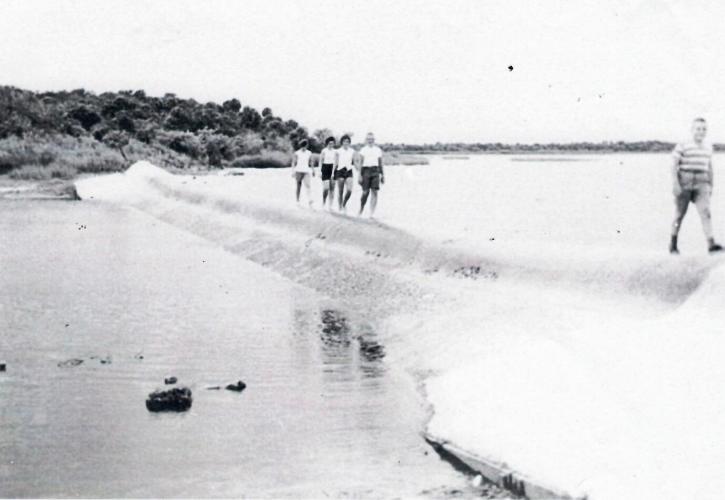

For example, the CCC had hoped to turn Myakka River State Park into a pristine area for hunting and fishing. To do this, they cast a giant net, called a seine, into the Upper Myakka Lake to remove the natural predators of fish. Water snakes, turtles, otters and other native species were all lost as a result of the the seining, and this process had a lasting detrimental impact on the ecosystem.

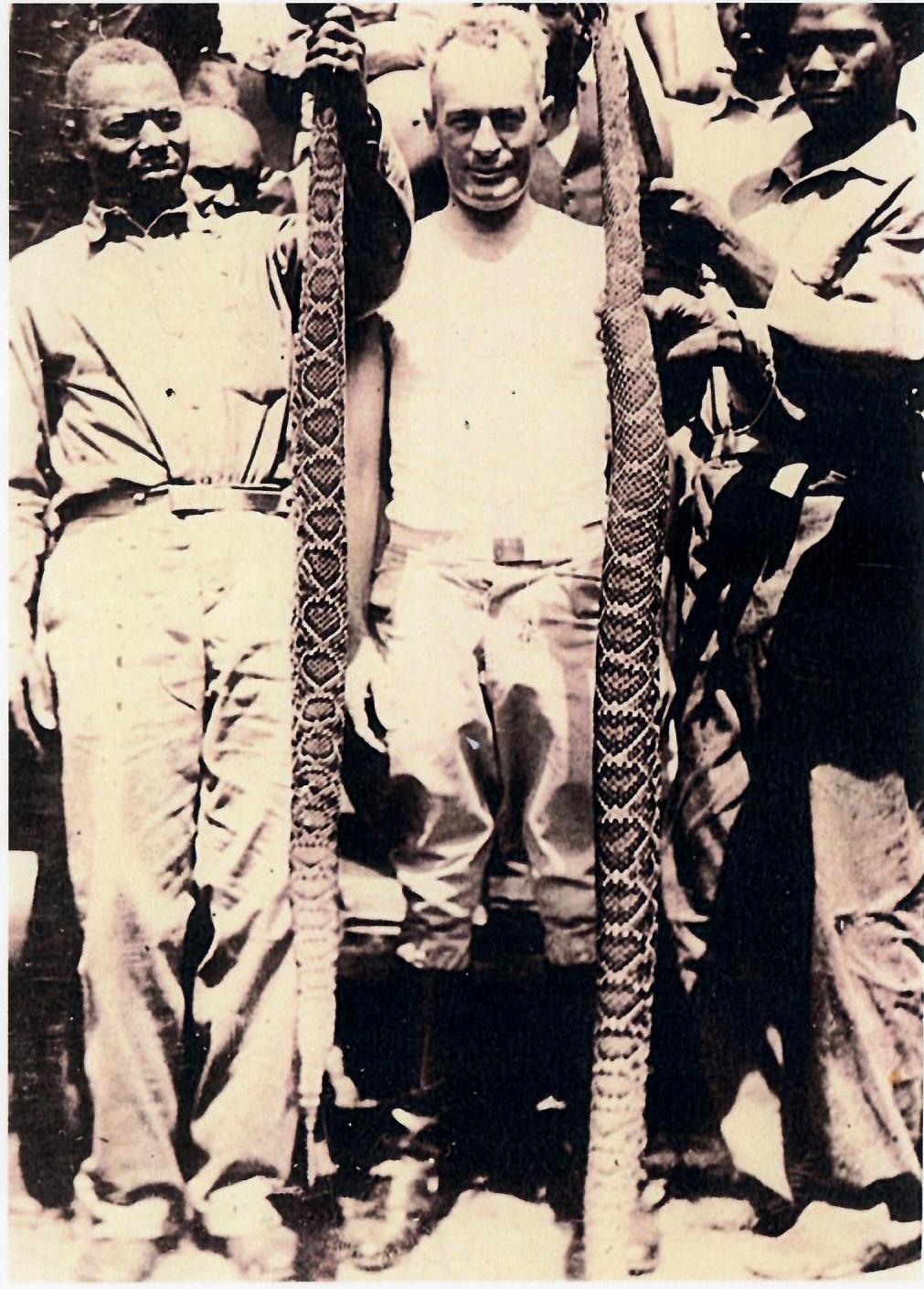

CCC members also killed native species as they saw fit. They killed every rattlesnake and alligator they encountered, which led to a heavy impact on the food chain of the Florida dry prairie and freshwater wetlands.

Other species’ populations became significantly unbalanced, and the entire ecosystem felt the devastating effects.

In other instances, the CCC instituted practices that they thought were helpful to the environment, but that we know were actually harmful.

The most obvious example of this was the CCC's strict no-burn system. They even had a parade through Sarasota celebrating the end of fires.

This was a frequent point of contention between the CCC and local ranchers and environmentalists. Ranchers often burned their lands to promote the growth of grazing grasses, but the CCC maintained that all fires were bad and, as a result, deprived the dry prairie of this important natural process.

Today, scientists know that the dry prairie naturally burns every two to three years, and these burns are essential to the proliferation of diverse, native wildlife. Partly because of this fire deprivation, the Florida dry prairie is now one of the most endangered ecosystems in North America. It is also the second-most biodiverse. The loss of a healthy dry prairie would mean the loss of incredible natural resources.

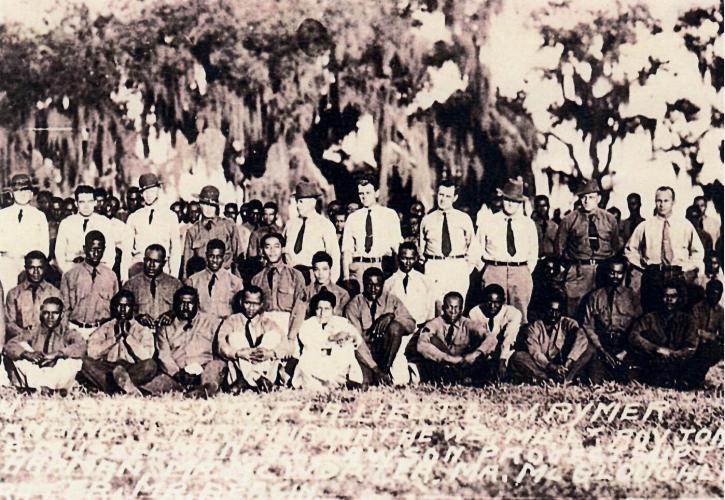

The CCC also has a complicated history of race relations. In the very beginning of the program, before it came to Myakka, the corps themselves were integrated. However, that was quickly overturned, and segregation within corps became the norm. While the CCC did have camps in Florida for both Black and Seminole men, African-Americans could comprise no more than 10% of the corps' total recruits, and they were often given the toughest assignments. These corps also faced discrimination from many of the communities where they were stationed, including Sarasota.

In 1935, it was announced that the all-white corps at Myakka was going to be replaced by an all-Black corps. At the time, most of the nation's residents lived on the east coast, but most of the required work was being done out west. Along with being segregated, Black corps also were required to stay within their own states, while white corps were permitted to work anywhere. By this time, Florida needed to send white corps across the country, but it still needed Black corps to continue working within the state.

The Fourth Corps Area, an Army-designed organizational unit that encompassed most of the southeastern U.S., was very aware of the backlash it would receive by bringing Black corps into communities that opposed them. To help ensure local cooperation, the Fourth Corps Area mandated that if a city voted against a Black corps, that city would lose its entire CCC operation.

At a town hall meeting in July 1935, Sarasota voted against the implementation of the Black corps. Within three days of Sarasota’s vote, the Army shut down all operations at Myakka River State Park and shipped the white corps elsewhere.

Not only did this halt the corps' land-improvement projects, but it also dealt a huge blow to Sarasota’s economy. Once again feeling the effects of the Great Depression, the city of Sarasota came to eventually accept a Black corps.

Starting in late 1935, Myakka's corps were primarily men of color. Despite local discrimination, they worked hard, day in and day out, to build the park's facilities and infrastructure. Without their work, the park would never have been completed. But in February 1941, Myakka River State Park officially opened to the public.

Thousands of people every year picnic, hike, bike trails, fish, and experience protected wildlife up-close and in-person.

The South and Log pavilions are frequently used for family reunions, weddings and baby showers. This is all thanks to those who transformed the Myakka River valley into Myakka River State Park.

The park continues to build and maintain structures and trails. Park staff and volunteers work to reduce the threat of invasive species that damage the ecosystem by outcompeting or reproducing faster than native wildlife.

AmeriCorps and other local agencies continue the legacy of the CCC, encouraging young employees to do conservation work and receive valuable job training.

CCC Accomplishments