Banding Songbirds at Cape Florida

My name is Liz Golden and I am the biologist at Bill Baggs Cape Florida State Park. My park is located at the southern end of Key Biscayne, a barrier island just a few miles south of Miami.

Encompassing 505 upland and submerged acres, the park is an oasis of native coastal habitats in a heavily urbanized region of the state. It is also an important stopover for many species of migrating birds. A bird banding project that began in 2002 has proven exactly how crucial the park is to seasonal migration.

A large percentage of the songbird species that breed in eastern North America fly through Florida to reach their tropical winter habitats. Traveling hundreds to thousands of miles, these migrating birds need to stop at natural sites like Cape Florida to rest and refuel, especially before they cross water. They also need to find a land refuge when bad weather occurs.

Restoration Following Hurricane Andrew

The Cape Florida that migratory birds use today is the result of large-scale habitat restoration that commenced in the 1990s. For decades, the park had been dominated by a non-native Australian pine forest that, while green, provided few resources for native wildlife.

In 1992, the Category 5 Hurricane Andrew destroyed that forest and forced the park to close for a year. But an unexpected benefit of the storm was that it allowed the Florida Park Service to start a multi-year effort to bring back the former native plant communities of Cape Florida.

In 1994, I joined the Florida Park Service as an OPS employee assisting with the restoration of Cape Florida. In 1996, I became the park biologist. Monitoring native plants and animals as they recovered from the effects of the hurricane was one part of my new job. I also recorded new plant occurrences and documented wildlife species as they discovered the park’s restored habitats. It was thrilling every time I could add a new species to the park’s post-hurricane list.

Not only was another part of the ecosystem back, but the increased diversity added to the park’s ecological stability.

The Start of the Cape Florida Banding Station

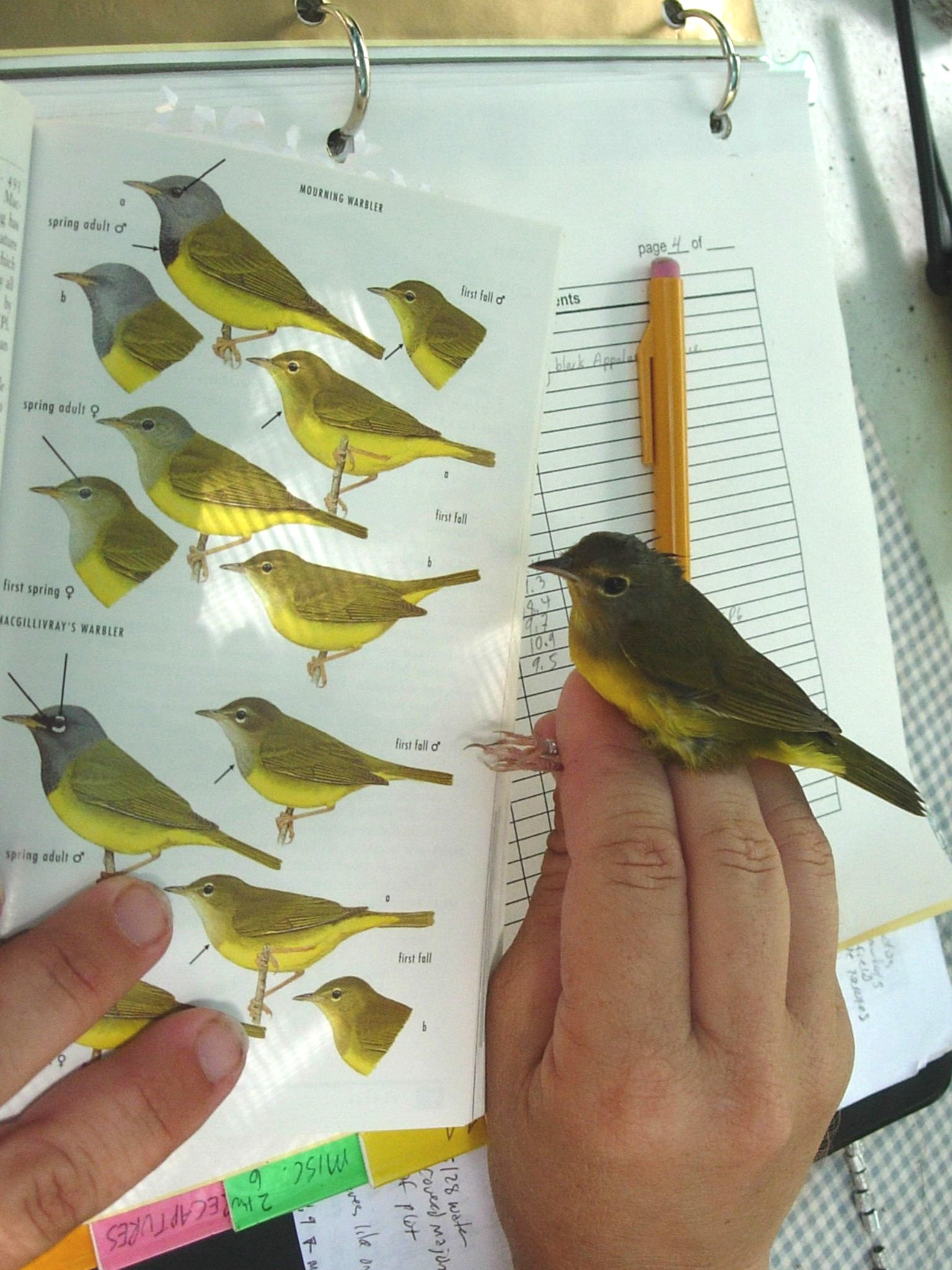

In 2002, local bird expert Michelle Davis initiated a bird banding project at Cape Florida. Bird banding is the practice of capturing a bird, placing a uniquely numbered aluminum band around its leg and then releasing the bird.

Banding allows an individual bird to be identified when it is recaptured or when it is found dead. Being able to identify individual birds permits the study of bird migration, their ranges and how long they live. Having a bird in the hand also allows for other information to be gathered, such as sex, age, size and weight.

Michelle wanted to study the use of restored habitat at Cape Florida by songbirds migrating south in the autumn. Additionally, she wanted to fill in a regional gap in knowledge about bird migration – no one else was collecting migration data in this part of the state.

With the appropriate license, permits and equipment, she set up a few nets in the replanted maritime hammock forest and started capturing birds. I became involved with bird banding at Cape Florida soon after. At first, I simply wanted to learn what bird species Michelle was catching. But then, as I saw how intriguing the collected data could be, I wanted to help expand the project.

For several years the station was managed by Michelle, myself and one other local bird expert. Gradually other bird-oriented and data-driven people volunteered to assist us.

What We Have Learned

The Cape Florida Banding Station, as the project is now called, has been operating for eight to 10 weeks every autumn season since 2002. Over 29,000 birds of 112 different species have been captured and banded. The majority of these species are typical small migratory songbirds – warblers, vireos, thrushes, buntings and flycatchers. Occasionally we have caught other types of birds – hawks, an owl and a heron species. Some routinely captured species are birds that live in the park year-round – Northern cardinals, common ground-doves, blue jays and common grackles. Some are vagrant birds from nearby Caribbean islands.

The data that has been collected thus far has proved that the restored plant communities at Cape Florida are benefiting migratory songbirds. Where formerly there was a forest composed almost solely of non-native Australian pine, today there is a mix of habitats in various stages of restoration – coastal grassland and strand, interdunal swale and mangrove swamp, beach dune and maritime hammock. These habitats provide a diversity of native plants that bear fruit and seeds and that host a variety of insects that birds and other wildlife feed upon.

Birds that migrate long distances need muscle and fat reserves to fuel their flight. Most birds that are recaptured at the station one to several days after their first capture reveal a gain in weight and show a visible increase in body fat and muscle tissue.

At the station, we have captured birds that we have banded in previous years. Known as “returns,” these birds are a mix of resident species and migratory species. The resident birds live in the park year-round, so it is not overly surprising that we recapture them. However, we have been startled to separately recapture two male Northern cardinals – one nine years after its first capture, the other 13 years after!

Birds that return to the park after breeding elsewhere are more intriguing. Fourteen different species of songbird have been recaptured one to eight years after they were banded at Cape Florida. Two things are revealed by this fact. First is that these individual birds – some weighing less than U.S. quarter coin – have made the journey between their breeding ground and Cape Florida at least twice and have survived the multiple hazards of migration. Some have made that trip up to 16 times. Second is that Cape Florida may be their wintering ground. Most of the “returns” are species that may spend the winter months in South Florida if they can find appropriate habitat.

Because we have recaptured these individuals in the same few acres of the park after a period of several months to several years, we can presume that Cape Florida is providing the wintering ground for these birds.

“Recovered” birds are birds that have been banded at one location and recaptured or found at another. These two locations can be a short distance apart or half a world away. Recoveries of banded birds can show not only what regions birds are moving to and from but also what routes and stopover sites they are using.

At the Cape Florida station, we have recaptured nine birds that were banded elsewhere. The closest banding site from which we have recovered a warbler is Wekiwa Springs, Florida, about 225 miles away. Two painted buntings (Passerina ciris) that we have captured were banded at sites in Georgia. Five warblers that we recovered were banded in northern states from West Virginia to Connecticut. One recovery was international – a gray catbird (Dumetella carolinensis) that had been banded three-and-a-half years before in Cuba.

Ten birds that we have banded at Cape Florida have been recovered elsewhere. Found two days to over two years after banding, these birds were either discovered dead or were recaptured alive, most in the eastern U.S. and Canada. The most remarkable of these recoveries are two Northern waterthrushes (Parkesia noveboracensis). One bird was recaptured alive in Puerto Rico, which is about 1,000 miles from Cape Florida. The other was recovered live in Newfoundland, Canada, more than 2,200 miles away. These recovered songbirds demonstrate the amazing distances that some of these small birds are traveling every year. They also show the connection that Cape Florida has to songbird breeding regions in northeastern North America and their wintering areas in the Caribbean.

The Future of the Banding Station

The Cape Florida Banding Station project will end in a few years. When it does, I will be content to know that the project provided very valuable information on songbird migration in South Florida. More importantly, I will be proud to know that the project has shown how Bill Baggs Cape Florida State Park - a relatively small area of restored native vegetation embedded in a larger urban area - is an important stopover and often a critical resource for migrating birds in North America.

About the Author

Elizabeth Golden is the biologist at Bill Baggs Cape Florida State Park. She has a Bachelor of Science degree in Natural Resource Management. She has worked for the Florida Park Service for 25 years. Over the years, she has developed her areas of expertise into native plant identification, wildlife monitoring, birding, banding songbirds and exotic plant control. She is motivated by a strong desire to help the park’s natural communities become and stay as healthy as possible and seeing the native plants and wildlife return and flourish to this restored habitat.

About The Biologists Tell the Story Series

In this series, we will learn a little more about our biologists, as they share stories of their work in Florida’s state parks. The leadership and scientific research our biologists provide is essential for our legacy of conservation and land management. This series is an opportunity to connect these projects to the places where we ensure the health and sustainability of Florida State Parks.